Eight images that tell the story of America

Bill Stettner

Bill StettnerA new exhibition of more than 200 photographs charts 300 years of image-making in the US, showing how the country’s history and photography have run in parallel.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington (DC

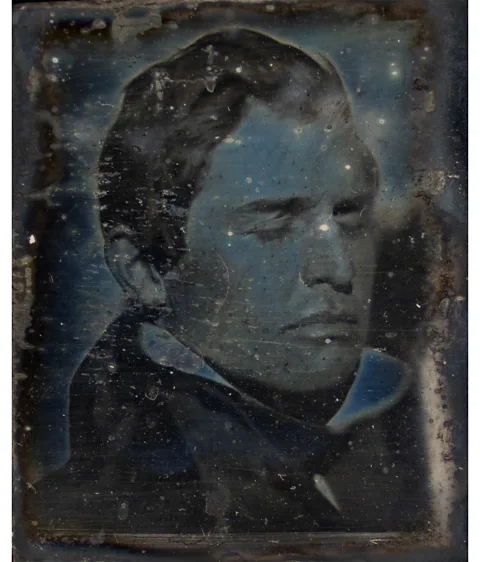

Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington (DCIn 1840, using a self-made copper plate, Henry Fitz Jnr produced one of the world’s first selfies, his eyes gently closed to prevent any blinking from spoiling the result. In creating this striking blue image, he was doing more than record his appearance; he was also documenting America’s first essays into an art form that would tell its story in radical new ways.

Fitz’s self-portrait, along with more than 200 other photographs, chart 300 years of image-making at the Rijksmuseum’s newest exhibition American Photography, Europe’s first comprehensive survey of this subject. Complemented by international loans, the exhibition showcases, for the first time, the museum’s own collection of American images, which it has been busy expanding since 2007.

For co-curators Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom, the exhibition’s starting point was to show the US through the differing perspectives of its photographers. Americans were “using this medium as we [the Dutch] used painting in the 17th Century,” Boom tells the BBC. “America and photography run parallel. The medium is so connected with the country.”

The exhibition has deliberately departed from a “top 100” approach, Rooseboom adds, stating “that would have been too easy”. Instead, works by icons such as Robert Frank, Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus sit alongside mementos, postcards and adverts – “surprisingly good images that nobody knows,” he says.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamA 19th-Century tintype (an image made on a sheet of metal) featuring a man and woman in front of a rustic barn is a case in point. The image was probably sold on the spot by a travelling tin typist “for a modest price”, explains Rooseboom. “Many people had just arrived and were living in the countryside, no big city nearby, so this was the only possibility of having your portrait taken.” The man stands proud, looking at the camera, but the woman’s head is bowed and she is looking away. “Sometimes you can sense that people were simply not used to being photographed,” says Rooseboom. “Nowadays, we’ve seen in magazines and movies how to pose elegantly.” This may be the only time in their whole life that they would be photographed, and the result, adds Boom, “would hang on the wall of the house where they lived forever”.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

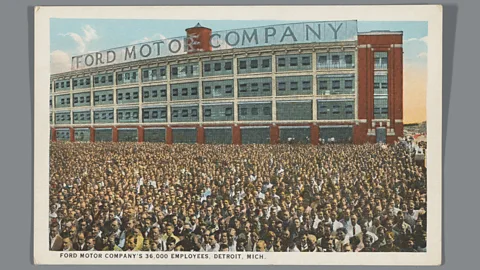

Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamBy contrast, a 1913 postcard featuring 12,000 employees of the Ford Motor Company in Detroit may have been the “most expensive picture that was ever taken”, quipped a newspaper at the time, as the factory had to shut down for two hours to assemble the staff. The image, the company boasted, was “the largest specially posed group picture ever made” and illustrates a turning point where industry saw the value in investing large sums in promotional photography. Taken in the year when Ford introduced America’s first moving assembly line and the US had become the world’s largest economy, the photograph also depicts the mass production that would shape the country.

The image’s reappearance in Ford marketing also made it an early example of photoshopping. While the same tinted faces swarmed in the foreground, the number of employees cited in the caption increased exponentially, and a building to the left was cropped out in one version and acquired extra floors in another. “Apparently, many photographers and their publishers had no qualms about abandoning their medium’s potential for realism,” write Boom and Rooseboom in the exhibition catalogue.

The James Van Der Zee Archive/ The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The James Van Der Zee Archive/ The Metropolitan Museum of ArtA decade on, the New York portrait photographer James Van Der Zee was also embellishing his work, drawing jewellery on to his subjects and retouching their faces to erase dark lines and wrinkles. “I put my heart and soul into them and tried to see that every picture was better looking than the person,” he said. As a black photographer working from his Harlem studio at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, his work records a period when black migrants fleeing the segregationist South were forging a new life for themselves in the urban North. For the first time, African Americans and other minority groups could be photographed by someone inside their community, and represented in a way that uplifted them. Van Der Zee’s Portrait of an Unknown Man (1938), for example, is carefully posed to suggest confidence. The outfit is elegant and the buttonhole daisy adds a dandyish flourish. It’s an image that reflects the aspirations and upward mobility of African-American people and the pride Van Der Zee had in his culture.

Irene Poon Photography Archive, Stanford University Libraries

Irene Poon Photography Archive, Stanford University LibrariesIt is the Chinese-American community that is the focus of the work of Irene Poon, who grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, where her parents, first-generation immigrants from Guanghzou, ran a herbalist store. A 1965 image features Poon’s sister Virginia in a local sweet shop, crowded out by Hershey’s and Nestlé bars. The letters “Nest” peep out from the densely packed shelves, reinforcing a sense that she is enclosed by this mass of graphic lettering. Beside her head a “Look” bar competes for attention, hinting at that other ever-expanding role for American photography: advertising − a sector in which the US was a forerunner. “Many of the 20th-Century artists started in advertising. It’s part of art history,” Boom says. “This whole field already existed, and the arts, and photography as an art form, draws from it.”

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamOne of the exhibition’s most powerful images, Stars and Stripes Forever? (1970) was created by New York advertising photographer Bill Stettner, who sought to elevate the status of commercial photography, and successfully campaigned for photographers to retain the rights to their work. “I’d like to think that what I’m doing, which is clearly commercial photography for advertising, is an art,” he told an interviewer for the 1980s television series World of Photography.

Stars and Stripes Forever?, his best-known work, was originally just a sample, made, he said, “out of necessity” to boost his portfolio following a financial downturn. The work takes its name from a patriotic march and features a US flag made from matches that has just caught fire, suggesting, perhaps, the fragility of the US and the principles that founded it. “Commercial photography is very often overlooked and not collected by museums, but it’s a fascinating field pictorially,” says Rooseboom. “You find the precursors of Modernism in advertising, but hardly anyone knows about this and [hardly anyone] has been collecting it or showing it in exhibitions.”

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond (VA

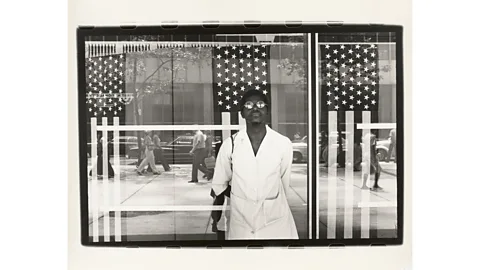

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond (VAIn the post-war years, mass immigration to the US brought new ways of thinking. the US took over from Europe as a cultural trendsetter, and photography was eventually accepted as an art form. Playful approaches to photography emerged, moving beyond documenting people and places to provoking emotion and inviting deep questions. Ming Smith’s America Seen Through Stars and Stripes (1976), created on the bicentenary of the Declaration of Independence, turns again to the flag inviting America to reflect on its history. By placing a figure in mirrored sunglasses in front of a shop window, she creates a disorientating mesh of reflective surfaces. The grid structure suggests incarceration but – in combination with the round glasses and the stars on the flag – also creates an abstract composition reminiscent of modern art. “She’s a careful observer, playing with all these layers in the image,” says Boom.

Smith explores the artistic potential of photography, experimenting with double-exposure, shutter speed and collage. In one version of this image, she paints on bold red stripes, altering this snapshot of the US with marks that resemble blood or flames. Smith’s work builds on the civil rights movement that preceded it and features activists such as James Baldwin and Alvin Ailey. She was the first woman to join the African-American photography collective the Kamoinge Workshop and the first black woman to have her work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Yet her demographic was largely overlooked by the art world. “I worked to capture black culture, the richness, the love. That was my incentive,” she told the Financial Times in 2019. “It wasn’t like I was going to make money from it, or fame – not even love, because there were no shows.”

Courtesy of Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie

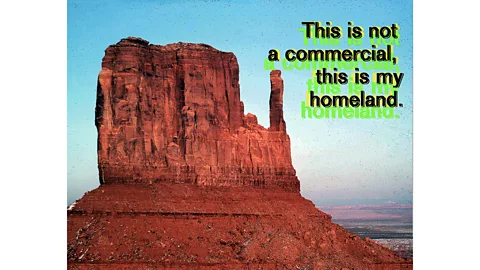

Courtesy of Hulleah TsinhnahjinnieThe political power of photography is also seen in the work of Native American (Seminole-Muscogee-Navajo) photographer Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie who uses the camera to correct misconceptions about Indigenous populations and to offer an alternative viewpoint on US history. “No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in, the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds,” she writes in a 1993 essay. “We document ourselves with a humanising eye, we create new visions with ease, and we can turn the camera and show how we see you.”

Tsinhnahjinnie’s captioning of a touristic image of Monument Valley, Arizona with This is not a commercial, this is my homeland highlights the commodification of American land, and uses what she calls “photographic sovereignty” to take us back to the very beginning and reclaim and retell the story of America. In combination with works such as Bryan Schutmaat’s Tonopah, Nevada (2012), which documents mining’s effect on the landscape of the American West, images like Tsinhnahjinnie’s tell a story of a beautiful land that means different things to different people: financial gain, security or a sacred space. As the camera has passed from hand to hand, the American stories have multiplied. “American photography is a much richer and wider field than even we knew,” says Rooseboom. “There’s still so much to be discovered.”

American Photography is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam until 9 June 2025. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue American Photography – America through Photographers’ Eyes, by Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom.

Source link