Confiscation in the American Revolution

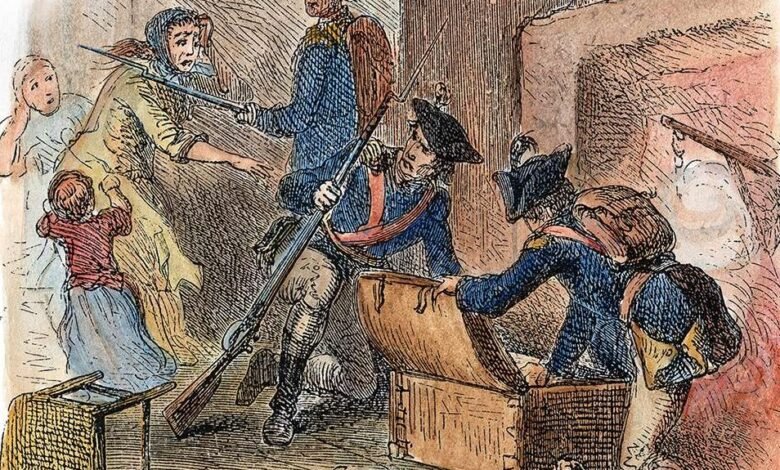

During the American Revolution, many revolutionary governments enacted confiscations, seizing property from Loyalists to raise revenue and punish those who opposed the revolutionary cause.

During the American Revolution, many revolutionary governments enacted confiscations, seizing property from Loyalists to raise revenue and punish those who opposed the revolutionary cause.

These allowed the seizure and sale of Loyalist property, which helped raise revenue for the states and solidify the revolutionary government’s power. They also served to criminalize dissent against the Revolution.

New York built one of the most robust property confiscation regimes, with the Provincial Convention creating Committees of Sequestration to seize property abandoned by Loyalists in 1777. These committees would auction off the property and send the funds to the state treasurer.

They argued that those who had aided the enemy had forfeited their property and the right to the protection. This led to the redistribution of property, with some Patriots benefiting from the seizure of Loyalist land.

New York’s most aggressive confiscation law, passed in October of 1779, was entitled “An Act for the Forfeiture and Sale of the Estates of Persons who have adhered to the Enemies of this State, and for declaring the Sovereignty of the People of this State, in respect to all Property within the same,” commonly called the Forfeiture Act (New York Laws, 3rd session, Ch. 25).

It included a list of New Yorkers who remained loyal to Great Britain and provided that these “offenders” had forfeited their right to property and were banished from the state. It also empowered the state to seize and sell their forfeited property

.The Commissioners of Forfeiture were charged with carrying out the 1779 Act. But in 1788, the state abolished the office of Commissioner of Forfeitures, transferring their power over forfeited property to the Surveyor General.

In 1802, the State Legislature passed “An Act to facilitate the discovery and sale of the estates of attainted persons” (New York Laws, 25th session, ch. 82). The act provided that any New Yorker to “discover and disclose” and provide evidence to the Surveyor General of an attainted estate — property forfeited and seized effectively for treason — that had not been sold, would receive 25% of the value when it was sold.

If the land was vacant, the person could opt to receive one quarter of the land in lieu of cash. The act also laid out rules by which the state would determine the value of forfeited estates on which people lived, and procedures by which occupants could purchase them from the state.

The lingering effects of these coercive state policies muddled the transition to consensual government.

Alexander Hamilton made his legal career by representing Loyalists in lawsuits trying to reclaim seized property. Hamilton believed the capital of these wealthy men would help build the new nation and sought to reintegrate into American society.

Resolving disputes over property confiscation was an important step in the transition from violent revolution into routine civil government.

New York University Professor Daniel Huslebosch will discuss his recent work, “Confiscation in the American Revolution: Taking Property, Making the State” via Zoom on April 2 at 7 pm (ET).

Daniel Hulsebosch is a legal and constitutional historian whose scholarship ranges from early modern England to the 19th-century United States.

This event costs $10 and is hosted by the Schenectady County Historical Society. You can register here.

Source link