Five ways to spot a fake masterpiece

Alamy

AlamyThe recent discovery of an art forger’s workshop reminds us of the long history of fraudulent artworks – here are the simple rules to work them out.

It’s everywhere: fake news, deep fakes, identity fraud. So ensnared are we in a culture of digitised deceptions, a phenomenon increasingly augmented by artificial intelligence, it would be easy to think that deceit itself is a high-tech invention of the cyber age. Recent revelations however – from the discovery of an elaborate, if decidedly low-tech, art forger’s workshop in Rome to the sensational allegation that a cherished Baroque masterpiece in London’s National Gallery is a crude simulacrum of a lost original – remind us that duplicity in the world of art has a long and storied history, one written not in binary ones and zeroes, but in impossible pigments, clumsy brushstrokes and suspicious signatures. When it comes to falsification and phoniness, there is indeed no new thing under the Sun.

On 19 February, Italy’s Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage uncovered a covert forgery operation in a northern district of Rome. Authorities confiscated more than 70 fraudulent artworks falsely attributed to notable artists from Pissarro to Picasso, Rembrandt to Dora Maar, along with materials used to mimic vintage canvases, artist signatures, and the stamps of galleries no longer in operation. The suspect, who has yet to be apprehended, is thought to have used online platforms such as Catawiki and eBay to hawk their phoney wares, deceiving potential buyers with convincing certificates of authenticity that they likewise contrived.

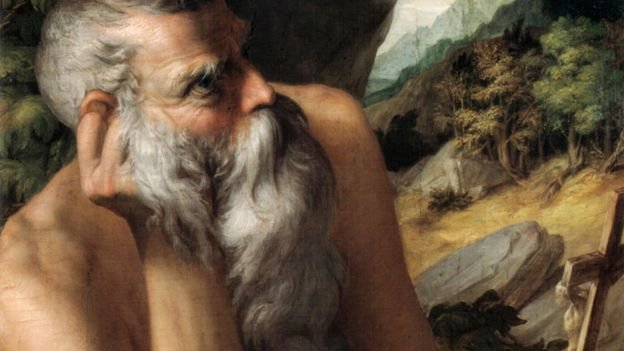

News of the clandestine lab’s discovery was quickly followed by publicity for a new book, due for release this week, alleging that one of The National Gallery’s highlights is not at all what it seems. According to artist and historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis, author of NG6461: The Fake National Gallery Rubens, the painting Samson and Delilah – a large oil-on-wood attributed to the 17th Century Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens and purchased by the London museum in 1980 for £2.5m (then the second-highest price ever paid for a painting at auction) – is three centuries younger than the date of 1609-10 that sits beside it on the gallery wall and is incalculably less accomplished than the museum believes.

Alamy

AlamyDoxiadis’s conclusion corroborates one reached in 2021 by the Swiss company, Art Recognition, which determined, through the use of AI, that there was a 91% probability that Samson and Delilah is the work of someone other than Rubens. Her assertion that the brushwork we see in the painting is crass and wholly inconsistent with the fluid flow of the Flemish master’s hand is strongly contested by The National Gallery, which stands by its attribution. “Samson and Delilah has long been accepted by leading Rubens scholars as a masterpiece by Peter Paul Rubens”, it said in a statement given to the BBC. “Painted on wood panel in oil shortly after his return to Antwerp in 1608 and demonstrating all that the artist had learned in Italy, it is a work of the highest aesthetic quality. A technical examination of the picture was presented in an article in The National Gallery’s Technical Bulletin in 1983. The findings remain valid.”

The divergence of opinion between the museum’s experts and those who doubt the work’s authenticity opens a curious space in which to reflect on intriguing questions of artistic value and merit. Is there ever legitimacy in forgery? Can fakes be masterpieces? As more sophisticated tools of analysis are applied to paintings and drawings whose legitimacy has long been in question (including several works attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, such as the hotly disputed chalk and ink drawing La Bella Principessa), as well as those whose validity has never been in doubt, debates about the integrity of cultural icons are only likely to accelerate. What follows are a handful of handy principles to follow when navigating the impending controversies – five simple rules for spotting a fake masterpiece.

Rule 1: Pigments never lie

Alamy

AlamyTo be a successful art forger requires more than technical proficiency and a misplaced ethical compass. It isn’t enough to approximate the dibby-dabby dots of a Georges Seurat, say, or the thick expressive swirls of Vincent van Gogh. You need to know your history as well as your chemistry. Anachronistic pigments will give you away every time and were the downfall of German art forger Wolfgang Beltracchi and his wife Helene, who succeeded in selling makeshift modernist masterpieces for millions before a careless squeeze of prefab paint onto their audacious palettes in 2006 sealed their fate.

Beltracchi, whose modus operandi was to create “new” works by everyone from Max Ernst to André Derain, rather than recreate lost ones, was always careful to mix his own paints to ensure they contained only ingredients available to whomever he was attempting to impersonate. He only slipped up once. And that was enough. Fabricating a wonky Der Blaue Reiter-ish red landscape of jigsawed horses that he attributed to the German Expressionist Heinrich Campendonk, Beltracchi reached for a readymade tube of paint, which he hadn’t realised contained a pinch of titanium white – a relatively new pigment to which Campendonk would not have had access. It was all investigators would need to prove the work, which had sold for €2.8m, was a fake.

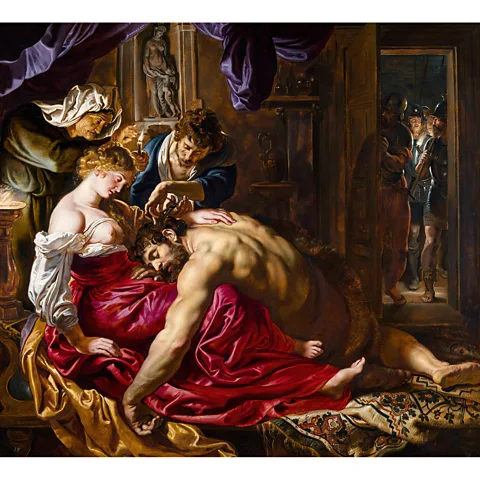

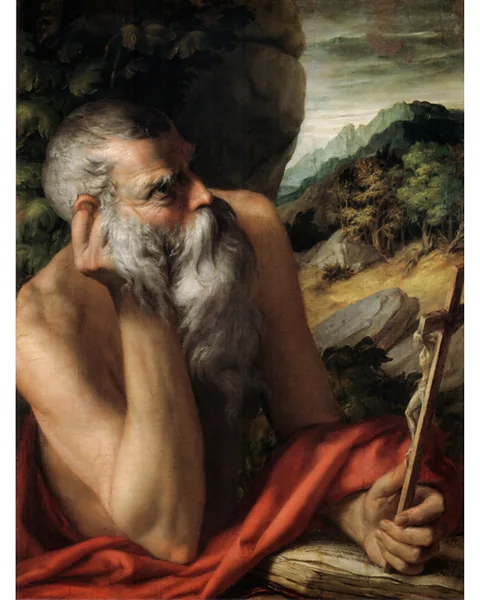

Beltracchi was unlucky. The gap between titanium white’s availability and its potential use by Campendonk was only a few years. On occasion, the divide is shockingly wide. Analysis of a Portrait of Saint Jerome, once attributed to the Italian master Parmigianino and sold by Sotheby’s auction house in 2012 for $842,500, exposed the prevalence throughout the work of phthalocyanine green, a synthetic pigment invented in 1935, four centuries after the 16th-Century Renaissance artist worked. Artists may be visionaries, but they’re not time travellers.

Rule 2: Keep the past present

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningan

Museum Boijmans Van BeuninganIt is uplifting to believe that one’s value, as a person, is not tethered to the past. Not so with art. A painting, sculpture, or drawing without a heavy history is not, alas, more inspiring for its lack of baggage. It is suspicious. Or rather, it should be. All too often, greed can interfere in the clear-sightedness of assessing the authenticity of a painting or sculpture. Things have histories we want them to have. That was certainly the case with a succession of phoney Vermeers that issued from the workshop of a Dutch portraitist, Han van Meegeren – one of the most prolific and successful forgers of the 20th Century. Desperate to believe that the miraculous appearance of canvases, including a depiction of Christ and The Men at Emmaus, might be lost masterpieces from the same hand that made Girl with a Pearl Earring and The Milkmaid, collectors were blind to the glaring absence of any trace of the paintings’ provenance – their prior ownership, exhibition history, and proof of sales. Everyone was fooled.

In authenticating the painting in the Burlington Magazine, one expert insisted “in no other picture by the great Master of Delft do we find such sentiment, such a profound understanding of the Bible story – a sentiment so nobly human expressed through the medium of the highest art”. But it was all a lie. In a remarkable twist, Van Meegeren eventually chose to expose himself as a fraudster shortly after the end of World War Two, after being charged by Dutch authorities with the crime of selling a Vermeer – therefore a national treasure – to the Nazi official Hermann Göring. To prove his innocence, if innocence it might be called, and demonstrate that he had merely sold a worthless fake of his own forging, not a real Old Master, Van Meegeren performed the extraordinary feat of whisking up a fresh masterpiece from thin air before the experts’ astonished eyes. Voila, Vermeer.

More recently, in a 2017 episode of BBC’s popular arts programme Fake or Fortune?, presenter Philip Mould’s long-held hunch that a painting he once sold for £35,000 was really a priceless original by the English Romantic artist John Constable – an alternative, and previously undocumented, view of the landscape artist’s 1821 masterpiece The Hay Wain – was dramatically confirmed after Mould and fellow presenter Fiona Bruce excavated long-buried financial records. Having traced the painting’s ownership back to a sale by the artist’s son, the team recalculated the canvass true value to be £2m, proving that some pasts are worth hanging onto.

Rule 3: Squint

Artists’ gestures – their simultaneously studied and instinctive brushwork and draughtsmanship – are nothing less than fingerprints writ large across canvases and works on paper. One artist’s lightness of touch and another’s sturdiness of stroke are exceedingly tricky to falsify, especially if you are conscious that every twitch of your brush and jot of your pen will be scrutinised by suspicious eyes and cutting-edge equipment. Pressure under pressure is hard to maintain, an obstacle that the British forger Eric Hebborn (who died under suspicious circumstances in Rome in 1996 after a career spent counterfeiting more than 1,000 works attributed to everyone from Mantegna to Tiepolo, Poussin to Piranesi) overcame with alcohol.

By all accounts, brandy was Hebborn’s tipple of choice for calming his rattling nerves. It allowed him to inhabit, without inhibition, the mind and muscle of whichever old master he was channelling. Whereas fakes from the hands of Beltracchi and Van Meegeren have since been found under closer inspection to be riddled with incoherent gestures, the fluidity of drawings falsified by the tipsy Hebborn in his heyday in the 1970s and 80s continues to confound the experts. To this day, institutions that possess works that passed through his hands refuse to accept they are all fakes, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s pen and ink drawing View of the Temples of Venus and of Diana in Baia from the South, a work it still insists is from the circle of Jan Brueghel the Elder. What do you think?

Rule 4: Go deeper

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen the analysis of pigments, provenance, and paintbrush pressure still leaves you stumped, it may be necessary to dive a little deeper. For 20 years since the 1990s, the authenticity of a still life purportedly by Vincent van Gogh was serially confirmed and refuted by experts. To some, the garish reds and submarine blues that echoed eerily from the bouquet of roses, daisies, and wildflowers didn’t have the ring of truth and seemed at odds with the painter’s palette. The absence of any ownership record for the painting didn’t help.

But an X-ray undertaken in 2012 put questions to rest when it revealed that the artist, pinching pennies, reused a canvas on which he had created another image entirely – one to which he makes explicit reference in a letter from January 1886. “This week”, Van Gogh remarked to his brother Theo, “I painted a large thing with two nude torsos – two wrestlers… and I really like doing that.” As if proleptically anticipating the ensuing scholarly wrangle over the work’s authenticity that the painting would in time trigger, the static tussle of the two athletes, trapped beneath paint for over a century, not only rescued the work from unfair allegations of illegitimacy, it created a kind of fresh composite painting, a vivid compression – a freeze frame of a restless mind forever scuffling with itself, desperate to survive.

Rule 5: It’s the little things that give you away

As a final safeguard in authenticating a work of art, run the spell check. Doing so would have saved the collector Pierre Lagrange $17m – the price he paid in 2007 for an otherwise compelling forgery of a small 12x18in (30x46cm) painting falsely attributed to the American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock. Famous for his drippy style, Pollock has a surprisingly legible signature, an unmistakable “c” before the final “k”. The skipped consonant would do more than expose a single forgery; it would shatter the reputation of an entire gallery.

The sloppy signature was just one of many missed red flags in works falsely attributed to Rothko, De Kooning, Motherwell and others that the Knoedler & Co gallery, one of New York’s oldest and most esteemed art institutions, succeeded in selling for $80m. The fraudulent works had been supplied by a dubious dealer who claimed they came from an enigmatic collector, “Mr X”. Just before the scandal erupted in the press, the gallery closed its doors after 165 years, while the suspected perpetrator of the fakes, a self-taught Chinese septuagenarian by the name of Pei-Shen Qian, who had operated from a forger’s workshop in Queens, vanished; he later turned up in China.

Source link