Great Gray Owls: Phantoms of the North

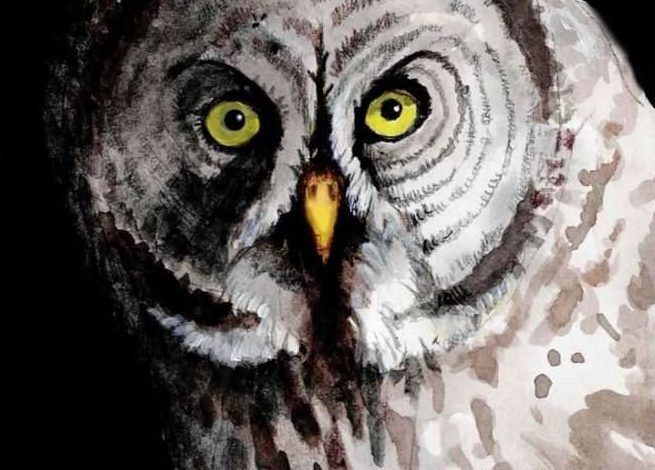

The great gray owl (Strix nebulosa) is a northern raptor that only occasionally graces our northeastern states. Also called the phantom of the north, these owls have large facial discs with alternating areas of light and dark gray, creating a concentric ring pattern around their yellow eyes.

The great gray owl (Strix nebulosa) is a northern raptor that only occasionally graces our northeastern states. Also called the phantom of the north, these owls have large facial discs with alternating areas of light and dark gray, creating a concentric ring pattern around their yellow eyes.

Beneath their face is a white “bowtie.” Despite this dapper feature, the owl’s luminous eyes, impressive size, and large talons give it a fierce appearance.

Great gray owls are the largest owls – from head to tail feathers – in the world, with females averaging around 28 inches long and males around 26 inches long. Their wingspan can reach over 5 feet.

Despite their stature, these owls weigh only about 2½ pounds on average – less than both great horned and snowy owls. Great gray owls’ hulking appearance is a trick of dense plumage which helps them endure cold winters farther north.

This circumboreal species lives in northern forests in Canada and the United States, as well as in Russia, Mongolia, and the Scandinavian countries. Great grays breed in dense conifer forests and hunt in open meadows and snow-covered bogs.

Their large facial discs help focus and funnel sound (much like cupping a hand over your ear), while the asymmetrical placement of their ears allows them to precisely locate the sound’s origin. With this highly sensitive hearing, they can track the movement of rodents tunneling beneath snow.

Great gray owls hunt both by flying low over open fields and by sitting and listening in low branches or on road signs, before “snow plunging” – bursting through the top layer of snow to catch rodents in the subnivean zone.

Great grays can plunge through nearly 18 inches of snow, at times requiring the strength to break through a top crust that can support the weight of a 175-pound person.

This feat doesn’t just require physical strength, but also a recalibration of where the prey actually is; the snowpack refracts sound, creating what researchers call an “acoustic mirage.”

A 2022 study published on this phenomenon in Proceedings of the Royal Society B found that the sound of scurrying rodent feet can be displaced up to 5 degrees from the actual location of the prey. The least distortion occurs directly above the source of the sound, which is why great grays tend to hover in place low to the ground before striking.

Their preferred diet consists of voles and lemmings. When these small mammals undergo population crashes, generally every 3 to 5 years, great grays may venture south en masse in search of food. One of the most notable irruption years was in the winter of 1978, when 154 owls were documented in New England and New York.

When great grays do grace our northeastern woods, they usually head back north in February and March. Males begin calling for mates in January and February.

Great grays don’t build nests, instead using tree cavities or nests abandoned by other raptors. Because of these nesting preferences, coupled with their size, great grays tend to thrive in forests with large diameter living and dead trees.

In April, a female will lay 2 to 5 eggs – depending on the availability of prey – and owlets hatch a month later. Both parents hunt to support the young, though males do most of it during incubation and when the owlets are young.

Black bears and great horned owls will sometimes prey on young great gray owls, but adults have no natural predators in North America. (In Europe, the Eurasian eagle-owl is the only known predator of adult great gray owls.)

Adult deaths are often the result of vehicle collisions or of consuming prey that has been poisoned by rodenticides.

I have yet to see this graceful giant, and due to its elusive nature, I may never get to. For me, part of the magic is simply knowing that this phantom of the north visits our winter woods from time to time.

Maybe one winter, without realizing it, I’ll pass beneath a great gray owl perched on a branch above me, its watchful eyes and powerful ears noticing everything before it takes to the air on silent wings.

Read more about owls in New York State.

Catherine Wessel is the assistant editor at Northern Woodlands. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.

Source link