In Defense of the Closet Drama

The production trap has been particularly disorienting for me due to my intense relationship with writing. I am one of those artists who uses their art as therapy (supplemental, to be very clear, to actual therapy with a licensed professional). Most of my major “gender evolution” moments came about through writing about gender. Because of this, writing cynically towards productions eludes me. I find myself continually running toward the controversial and uncommercial. Recently, coming out of my two-year writer’s block, I wanted to write about my experience with sexual assault. As I fell in love with what I was writing, I also became convinced that it wouldn’t be ethical to actually produce the play due to its content (though I am flexible on this point; it would require the right intimacy director). Still, it felt vital to me—and vital plays are the sort of plays I want. So, I consciously set the production trap aside and began to accept that I was writing a closet drama.

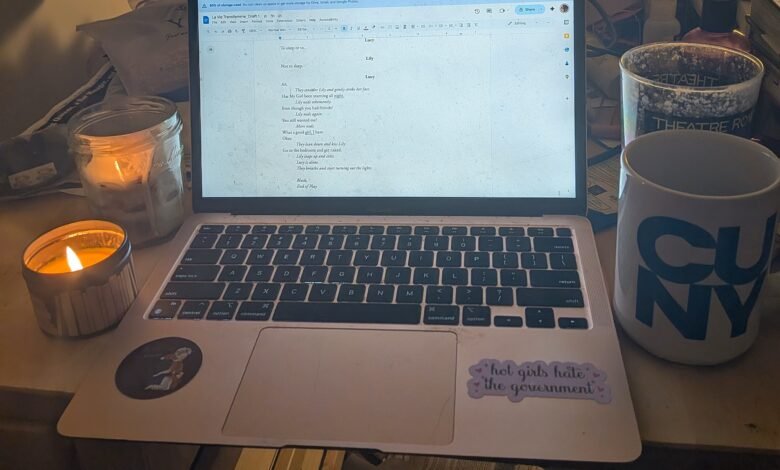

This change of form changed the way I wrote, not just what I was writing. It freed me to create more ambitious work. Suddenly, I could use parts of the page and elements of writing that were previously not available to me as a playwright. As I continued to write I Won’t Be Your Daddy or Rape Play, I had new toys to experiment with, like footnotes. In one monologue, for example, I used three footnotes: one to cite a primary source I quote in the play, one writerly aside about a girl who ghosted me, and a citation of a song that is quoted.

I also started playing around more intentionally with the stage directions now that the “audience,” not just my potential collaborators, could see them. For example, here are my opening stage directions from a piece called School Play or Why Am I Sending You This Email:

Lights Up

An Acting Class

Maybe there are other people but there are four who are important

There is You

You are an 18 year college student who is secretly a girl

So Secretly, in fact, that even you don’t know yet

You know you’re something tho

And You’re About to Come Out As “Bi” or “Queer” or “Gay” or “Faggot”

You were homeschooled

This is your first time being away from home

You weren’t cool in high school

Until senior year

When you were

And that gave you confidence

And now You are enrolled at the most prestigious theater education program in the State

You feel very proud

And scared

You want friends

Maybe these people around you will be your friends

There is the Friend Who Is Also Secretly a Girl

The first time you see a picture of her you think she’s a girl

Throughout the play she will do different things to disguise the fact that she is also secretly a girl

And she is able to fool a lot of people

Even You

But to hide she becomes monstrous

And that is sad

Her story in this play is a sad one

Don’t let the lines confuse you

Her story is also a tragedy

In both of these plays, I speak with the audience more directly than I could in a piece that is not a closet drama. It is possible that these experiments won’t work, for me or for you, but I believe that removing the need to be produced or performed can allow playwrights to create with real joy, energy, and passion again.

What I describe in this essay are experiments to push the art form of theatre forward. Experiments help us reinvent our own work and reimagine the entire canon. They are also, largely, non-commercial due, in large part, to the limitations on risk-taking. Both producers and audiences make their choices in response to the high cost of tickets—across both for-profit and nonprofit theatre—which means each play needs, to some extent, to be a “sure thing.” If you want to stay booked, writing experiments probably aren’t the easiest way to do that. Yet without theatrical experiments by playwrights, we’ll stay in one place forever theatrically.

A closet drama removes gatekeepers. If I have access to writing materials, I can write a closet drama.

Closet Drama as an Avenue for the Political Play

If I wrote a play tomorrow about this current moment, it wouldn’t reach the stage until the moment had passed. That’s true even if every gatekeeper lines up behind me; the process of getting new work on stage in this country is achingly slow. Functionally, this means that it is very, very difficult for of-the-moment work to reach a major stage while it is still of-the-moment.

As an example, I want to read what Minneapolis-St. Paul playwrights have to say about what’s happening to their city now, not see it in five years when the crisis is no longer (one hopes) ongoing. I’m sure there will be pieces about immigration coming down the pipe, but they will struggle to meet the moment because many moments will pass between when the play is written and when it is produced. This will likely mean that these plays don’t hit as hard, that their political content has been defanged—if not consciously then just as a result of time passing.

Many of us found ourselves drawn to the arts because of the political potential of art, but that potential is limited first by the timeline for getting that work seen. I contend that this timeline causes many playwrights to stop writing about the specific to write about the general; in New York City—which is the scene I am most familiar with—theatres produce many plays that are generally about what it is like to queer, a person of color, etc. but very little about what it is actually like to live in this specific, contemporary moment.

The political environment also limits theatre. I’m a communist trans woman; I’d be surprised if Trump’s government gave me a grant to do anything but kill myself. As Davey Davis has written, the new National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) guidelines effectively bar all trans artists from federal funding. Soon, we could see attempts to withhold federal funding from any company that does trans plays or employs (and respects) trans people. If we extend this thinking, the same could likely go for any work or artist considered too “woke,” which could lead theatre administrators to become even more conservative when it comes to programming. Any politically challenging plays that manage to get through the already broken development process could become political targets for the government and right-wing media. This is also, of course, not new. Senator Jesse Helms began a war against experimental political and queer artists in 1989, which led to huge cuts and attacks on the NEA. That Trump makes Helms look like a moderate just shows how dire the current situation is.

A closet drama removes gatekeepers. If I have access to writing materials, I can write a closet drama. In this sense, the closet drama defies and rises above the pragmatic demands of the theatre industry to focus on the artistic and political demands of the theatrical form.

Existing tools help playwrights have more avenues distribute their closet dramas. New Play Exchange exists as a library for closet dramas. Readers engage with writers’ words without the need for a production to “make it real.” Compare this to the current working model, which takes months—or, likely, years—to get the same play in front of an audience and provide enough outside pressure that likely the most radical pieces of the play would die around the rehearsal room table.