‘Sodomy’ & Colonial America Crime and Punishment

The early conquest of overseas territories led to the application of European directives regulating life in the colonies.

The early conquest of overseas territories led to the application of European directives regulating life in the colonies.

Imposing rules on sexual behavior served as tools of social control and dominance. Prohibitions on “sodomy” entered legislation in New England and New Netherland with severe penalties attached.

Although castigated by church leaders and civil authorities, same sex relations between Europeans themselves or between them and Indigenous People were common amongst individuals living in relatively isolated settlements. For many critics, the lived experience of colonial society was plagued by unimpeded sexual desire and depravity.

English Puritans

England introduced the death penalty in the American colonies. The first recorded instance took place in 1608 when George Kendall of Virginia was executed for allegedly plotting to betray the English to the Spanish. In 1622, the first legal execution of a felon named Daniel Frank occurred in Virginia for the crime of theft. The colony of Connecticut followed its English predecessors (the Buggery Act was adopted in 1533 during the reign of Henry VIII) by making sodomy a capital crime in 1642.

Language matters in this context. The term “homosexuality” was not introduced until 1868 by the Vienna-born Hungarian journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny and first used in English by John Addington Symonds in his 1891 reflections on the problems of modern ethics. The seventeenth century spoke in terms of “sodomites” with a Biblical reference to Sodom and Gomorrah.

Sussex-born William Plaine was one of the early English settlers reaching Guilford, Connecticut, in 1639. A married man, he would be the first person to be executed in the New Haven Colony. On June 6, 1646, he was hanged for allegedly sodomizing and corrupting more than a hundred young boys.

It was rumored at the time that he had fled to America to escape prosecution in England. John Winthrop, the first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, supported the execution calling the accused a “monster in human shape.”

In New England, sodomy was feared as an impurity that would pollute the sanctity of Puritan culture. As Church and State were synonymous, its laws were derived from Old Testament sources.

In order to prevent New Jerusalem turning into a New Sodom, Puritans demanded the death penalty for the offense. The same punishment was prescribed for rape or adultery, but an adult male sexual relationship was considered the most “abominable unnaturelle sinne.”

These laws however were rarely applied as magistrates opted to hand down lighter sentences. The first trial ever for sodomy documented in the Records of the Colony of New Plymouth concerned John Alexander and Thomas Roberts. The men were found guilty of “lude behaviour and uncleane carriage one [with] another, by often spending their seede one upon another.”

Alexander received a whipping, was burned on the shoulder with a hot iron and banished from the colony. Roberts, an indentured servant, was whipped and returned to his master. He was barred from ever owning land in the New Plymouth colony.

In spite of a repetition of thundering sermons of revulsion, few convictions have been recorded for the “crime.” Executions were rare. It appears that same sex activity was both more frequent than represented by the court records and accepted as a fact of life in colonial society.

Frontiersmen were isolated for long periods of time away from women. Living in all-male communities, many of them would have participated in sexual activity.

To a theocratic government, the undermining of religious principles was a serious crime. William Plaine had compromised the concepts of marriage and pro-creation, but the most “wicket” sin was his outspoken atheism. His alleged “questioning whether there was a God” was interpreted as a defiance of Puritan beliefs. Atheism was more threatening than sodomy in the regime’s struggle to maintain social discipline and obeisance.

Dutch Sodomy Laws

Dutch Sodomy Laws

The Dutch Republic was a loosely organized federation of seven provinces, each with its own administration and legal provisions. Some provinces had anti-sodomy statutes, but the Republic’s most powerful province of Holland did not formulate a ruling until 1730. But even in the absence of explicit criminal laws, a range of other regulations could apply and verdicts against culprits often referred to such authorities.

The most validated of those dated back to the era that the Low Countries were part of the Habsburg Empire under Charles V. Its legal code was summarized in Constitutio criminalis Carolina of 1532. Article 116 required the death penalty for sodomy.

In 1554, Flemish jurist Joost de Damhouder published his Praxis rerum criminalium, a manual on the practice of criminal law that was translated in various European languages. In article 96 he demanded the death penalty for crimes “against nature.” Such acts could be perpetrated between men, between women, with animals or with non-Christians. Anal intercourse was to be punished with burning at the stake. The same legal principles would apply in the colonies.

In New Amsterdam, Jan Creoli was executed at the time that Willem Kieft served as Director of New Netherland. An enslaved man of African descent, he had been handed over to the authorities by fellow slaves for sexually assaulting a ten-year-old boy named Manuel Congo.

The New Netherland Colony Court recorded the act as an abomination for which the prisoner was sentenced to be publicly choked to death and then burnt to ashes. The execution took place on March 25, 1646. Congo was flogged for his part.

At home and in the colonies, public display of executions was part of a criminal justice system that relied upon fear of retribution. An execution was a triumph of the law and a warning to potential wrongdoers. Maybe Willem Kieft was trying to save his collapsing career from accusations of incompetence when he judged the Creoli case to be an “existential” threat to the colony.

Such a crime, he argued, can “not be tolerated or suffered, in order that the wrath of God may not descend upon us as it did upon Sodom.” His uncompromising position did not save his job.

Peter Stuyvesant arrived in New Amsterdam in the year of William Plain’s execution in the New Haven Colony. The new Director-General made it his mission to rebuild the moral state of the colony.

Under New Netherland’s legal provisions sodomy was punished with death, but here too the law was rarely carried out. In fact, just one execution had taken place before Stuyvesant was challenged to stabilize the disorderly colony.

Moral Mission

During Willem Kieft’s time in office tensions between colonists and Munsee speaking people (Lenape) had turned violent. While indigenous inhabitants resisted the repressive nature of his regime, Kieft was

paranoid about conspiracies. He was neither a diplomat nor an administrator but a soldier whose demanded strict obedience – or else.

His costly “war” lasted for two years and caused irreparable damage in the relationship between newcomers and Native Americans. The future of the colony was at stake.

On Stuyvesant’s arrival, New Amsterdam was a multi-lingual melting pot city with livestock roaming the streets and dockside drunken brawls spilling out of seedy taverns. The Director had to put up with practical difficulties as the cash-strapped West India Company (WIC) barely responded to his pleas for men and material.

A hard-line Calvinist, he was shocked about the city’s moral state and immediately enforced a slew of injunctions against drunkenness, violence and immorality. In no way was he going to turn a blind eye to sodomy.

Educated in the Netherlands, Harmen Meyndertz van den Bogaert was a surgeon-barber (a common combination at the time) when he arrived in New Amsterdam about 1630. He moved up the Hudson River to Rensselaerswijck and participated in the colony’s fur trade.

Educated in the Netherlands, Harmen Meyndertz van den Bogaert was a surgeon-barber (a common combination at the time) when he arrived in New Amsterdam about 1630. He moved up the Hudson River to Rensselaerswijck and participated in the colony’s fur trade.

As a physician and trader, his career blossomed. Married with four children, he was promoted to the post of commissary (business agent) at Fort Orange. In the winter of 1634, he joined a WIC mission negotiating with the Mohawk for beaver pelts. It was a sensitive diplomatic challenge in which the Dutch had to contend with competing French interests in the profitable fur trade.

During the expedition, Van den Bogaert penned a daily journal, later published as A Journey into Mohawk and Oneida Country, 1634-1635 (2013, edited by Charles Gehring and William Starna). The first written description of the Mohawk Valley, he recorded the daily activities of his party, sketched the geography of the land and described aspects of Iroquois life and rituals.

A word list added to the end journal represents the earliest known philological research into the Mohawk language.

Toward the end of 1647, Van den Bogaert was caught having sex with his young (“under-age”) slave named Tobias. Both were jailed at Fort Orange. Aware of the fact that the punishment for sodomy in the colony was death, they escaped and fled north for the Iroquois lands which Van den Bogaert had explored in the past.

A posse of WIC soldiers was dispatched to bring the couple back to New Amsterdam and face justice. They were found in a Mohawk village where a battle ensued in which considerable damage was done (local Mohawks later sued the Company for damages which were paid out of the sale of Van den Bogaert’s Manhattan bowerie, or farm). The two men were returned to prison.

A letter was sent to Peter Stuyvesant who dispensed justice in New Amsterdam. The latter postponed the case at Fort Orange until the spring. Convinced that the unforgiving Director-General would impose the death penalty, Van den Bogaert made another attempt to escape. Whilst crossing the frozen Hudson River, he fell through the ice and drowned. The fate of Tobias is unknown.

Slavery

In May 1660, four years before Peter Stuyvesant officially handed over New Amsterdam to the English, a sodomy case of an indentured servant and a married soldier was brought before the council of the New Netherland Colony. Brussels-born Jan Quisthout van der Linde was found guilty of sodomizing his servant Hendrick Harmsen, an orphan from Amsterdam.

His punishment was severe. He was sentenced to be “stripped of his arms, his sword to be broken at his feet, and to be then tied in a sack and cast into the river and drowned until dead.” The site of public executions at the time was Het Marckvelt (the Market Field) on Manhattan’s southern tip. The council sentenced Hendrick Harmsen to be privately whipped and sent to “some other place” by the first opportunity even though it was acknowledged that the youngster had been raped.

Quisthout’s treatment seemed particularly cruel. Torture at the hands of executioners had become part of the criminal justice system in Europe by the sixteenth century. The practice was not an act of blind savagery or an expression of rage. Every aspect of the process was carried out with military precision and the pain to be inflicted was measured carefully.

Doctrinal support of the Church for capital punishment was unequivocal. It was agreed that the executioner was not in a damned state as he implemented the judgment of just authorities.

In New England William Paine had been executed to protect the unity of Puritan society from atheism and disintegration. The death penalty was a defense mechanism. Dutch colonial officials came down hard on enforcing legal proceedings when dependent minors were involved, but seemingly ignored same sex relationships that existed among consenting adults.

Economics in New Amsterdam trumped religion. The settlement consisted of a mixed mass of incomers driven by the need to survive. Toleration was an essential condition of being, not an abstract ideal, even if this implied the acceptance of “sinful” behavior.

It is significant that two of the recorded sodomy cases involved African slaves. Brought over from the Caribbean, slaves were a vital part of the colony’s economy as they helped building Fort Amsterdam; developed the colony’s infrastructure and worked on farms; and protected settlements from attack by Native Americans.

Without their involvement, New Netherland might not have survived as long as it did. To abuse a member of its crucial workforce was considered a strike against New Amsterdam itself.

The executions during the final years of Dutch rule may have been a last attempt to restore order and discipline and save the colony from collapse.

The Stonewall Inn

When the English took possession of New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant retired to a plantation he had purchased from the WIC in 1651. Having withdrawn from politics, he devoted his energy to developing the Stuyvesant Farm or Great Bowery. Part of the original purchase, mainly along the Bowery and Fourth Avenue, remained in the hands of his descendants until the later twentieth century.

Today, Greenwich Village has countless reminders of presence of the Stuyvesant dynasty. Peter himself was buried at St Marks-in-the-Bowery Church.

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in the West Village holds a prominent place within the gay movement’s history and its fight for civil rights. From June 28 to July 3, 1969, patrons of the inn and members of the local community were involved in resisting a large police force during a brutal raid of the tavern.

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in the West Village holds a prominent place within the gay movement’s history and its fight for civil rights. From June 28 to July 3, 1969, patrons of the inn and members of the local community were involved in resisting a large police force during a brutal raid of the tavern.

Homosexuality was illegal then and there were ordinances against cross-dressing. The confrontation turned into a riot.

The violent event was a catalyst for the explosive growth of the gay rights movement. In the immediate aftermath the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was founded in New York and many similar groups were formed nationwide.

Just a year after the Village stand-off, the first Pride marches took place in Manhattan, Los Angeles and Chicago. The irony is that these rights were won in an environment that used to be Peter Stuyvesant’s manor, but it now the Stonewall National Monument.

(Editor’s Note: The death penalty for homosexuality continues in at least seven countries.)

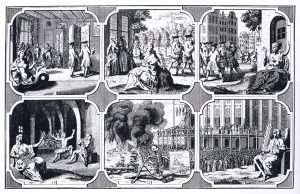

Illustrations, from above: “Timely punishment depicted as a warning to godless and damnable sinners,” Engraving depicting the Dutch massacre of homosexuals published in Amsterdam, 1731 at the time of the 1730 persecution of homosexuals that took place in the Dutch Republic, starting in the city of Utrecht in 1730; 1601 edition of Joost de Damhouder’s Praxis rerum criminalium (1554), the first comprehensive study of criminal procedure; Burning of five monks for sodomy in Ghent, Flanders, on June 28, 1578; Stonewall Inn is draped with a reminder of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising.

Source link